HAWAIIAN CHIEFLY REGALIA

Most of the great chiefly families of Hawaii retain in their possession the insignias

of rank inherited from their distant ali’i ancestor, usually a high chief or king.

Typically, the items passed down are weapons and chiefly vestments worn by the Ali’i.

These include the whale tooth necklace (lei niho palaoa), made up of a hook-

Lei Niho Palaoa (Whale Tooth Necklace).

This one is in the collection of the British Museum.

The most prized items of all were those constructed of feather work. Hawaiian feather work was at one time restricted only to the royal family, high chiefs, lower chiefs (using less valuable feathers) and images of the gods (such as Kukailimmoku). Common people did not have the right to wear feathers.

`Aha`ula (Feather Cape)

Chiefess Liliha and Chief Boki.

(c. 1810)

The complete regalia of the high chiefs would include a feather malo (loin cloth),

ka`ei (feathered girdle or belt), `aha`ula (feather cape), mahiole (helmet), kahili

pa`a lima to be carried in the hand, kahili lele carried by a personal attendant

and used as a fan or fly-

EHEUKANI

DESCRIPTION

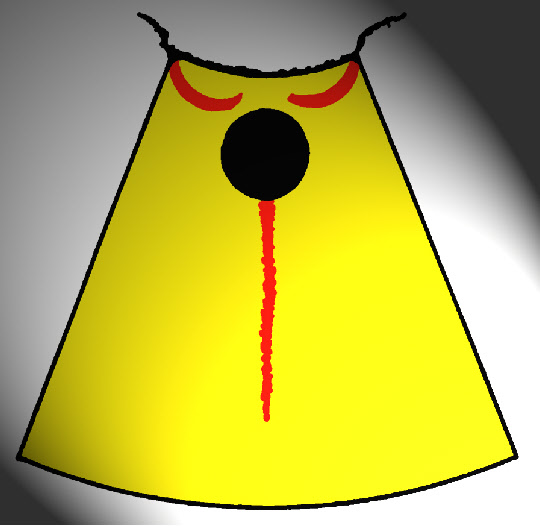

“Eheukani” was the name given to the `aha`ula (feather cape) belonging to Solomon

L.K. Peleioholani (1842-

Aha`ula No.106

A cloak said to have been destroyed in the conflagration caused accidentally in the attempt of the Board of Health to stamp out the bubonic plague in the Chinese quarter of Honolulu. At the time when the claims for losses caused by this great fire were presented to the Commission appointed for the purpose, my assistant, Mr. Allen M. Walcott, obtained from the claimant, Peleioholani, a carpenter by trade, the following particulars : The cloak was called “Eheukani” and was made in the time of Keeaumoku (the father of Kaahaumanu) and finished shortly before the battle of Mokuohai (July, 1782) between Kamehameha and Kiwalao. Keeaumoku's wife gave it to Peleioholani's Grandmother.

Principally mamo feathers with a small crescent of red iiwi in each upper corner; between the shoulders a round spot of black oo feathers, from which a line of red iiwi led down to a trifle below the middle of the cloak. The cords at the neck were of human hair, an unusual thing.

It must be remembered that the design as well as the following measurements are from the description given to Mr. Walcott by Peleioholani and are of course only approximate. They are worth recording as differing from any robes described. Length, about 4 feet 9 inches; neck measurement circumference at bottom about 5 feet 8 inches. It is a matter of tradition that 27,000 birds were captured to furnish the feathers for this cloak.

In the left side were seven spear holes that were never patched, and about which were blood stains. Keeaumoku was severely wounded in this battle, and it was rather a fancy with the old chiefs to retain the honorable scars in the ahuula, as in the cloak given by Kamehameha to Vancouver to be taken to England for King George.

-

LOST IN FIRE

“Eheukani” was lost, and presumed destroyed, along with other chiefly regalia and precious possessions belonging to Solomon Peleioholani during the great Chinatown Fire of 1900. The history of the cloak and the story of how it disappeared was told in a newspaper article from 1902.

Solomon L. Peleioholani, one of the highest surviving chiefs of the Hawaiian race, the man who stood before Lunalilo when he was crowned King of the Hawaiian Islands, wearing the famous cloak, helmet and necklace, and also stood before Kalakaua at the latter’s coronation and received the foreign representatives.

His father’s name was also Peleioholani and his mother’s name was Piikeakaluaonalani, his great grandfather being the high chief Keeaumoku, one of the ablest supporters of Kamehameha I.

It was in the battle of Mokuoha, which was fought between Kamehameha and Kiwalao

in July, 1783 that Keeaumoku distinguished himself and performed a deed which has

been one of the greatest treasures handed down to Peleioholani. The death of Kiwalao

in that battle gave Kamehameha prestige over the entire island of Hawaii. It was

Keeaumoku who killed Kiwalao in a hand-

Keeaumoku went into battle arrayed in his magnificent mamo feather cloak and helmet,

spear, hair necklace and feather baldric, seven feet long. Upon his hands were the

terrible lelamanos, or battle gloves. Each glove was formed of two strips of wood,

each strip being fitted with four shark’s teeth, sharpened to a keen edge. These

were fastened to the middle fingers of each hand with thongs. In a hand-

Keeaumoku and Kiwalao, uncle and nephew, came face to face during the battle and

were about to commence the hand-

The blood-

The blood stained cloak and helmet were closely tied to the fortunes of the Kings

of Hawaii. When Lunalilo was crowned King it was Peleioholani who stood in front

of him clothed in the royal feather emblems of rank, holding the sword of the crown.

The sword was given into the keeping of Lunalilo when he had taken the oath. The

last time the famous cloak and helmet were worn in public was at the coronation of

King Kalakaua on February 12, 1883. Peleioholani and Kekuiapoi, son of the high chiefess

Keano, the two highest chiefs in attendance at the ceremonies, the great grandsons

of Kamehameha-

The history of the heirlooms tells also of Peleioholani’s noble ancestry and his claim to the title of high chief. It was because he was a high chief that, while a boy of about ten years, he was sought by Kamehameha IV and his consort Queen Emma, and taken by them to Honolulu to be brought up as the companion of the Prince of Hawaii.

-

UNSOLVED MYSTERY

And so the story goes. But a mystery remains. Was “Eheukani” really lost in 1900? Or was seized from the warehouses during the looting which accompanied the Chinatown Fire? Perhaps Eheukani and the other possessions of Solomon L.K. Peleioholani were not burned in the fire, but were saved by looters and are still in existence. Feathered cloaks were in high demand from collectors around the world even at that time. They would have fetched a good price from private collectors, such as those who had already tried to buy Eheukani from Peleioholani’s family, but failed. It is our hope the Eheukani is today in a private collection and will one day be returned to our family.

The `Aha`ula (Feather Cape) “Eheukani” -

Click to read original Bishop Museum report.